What Happens When There's No Number

The invisible cost of governing without measurement

BEFORE THE NUMBER

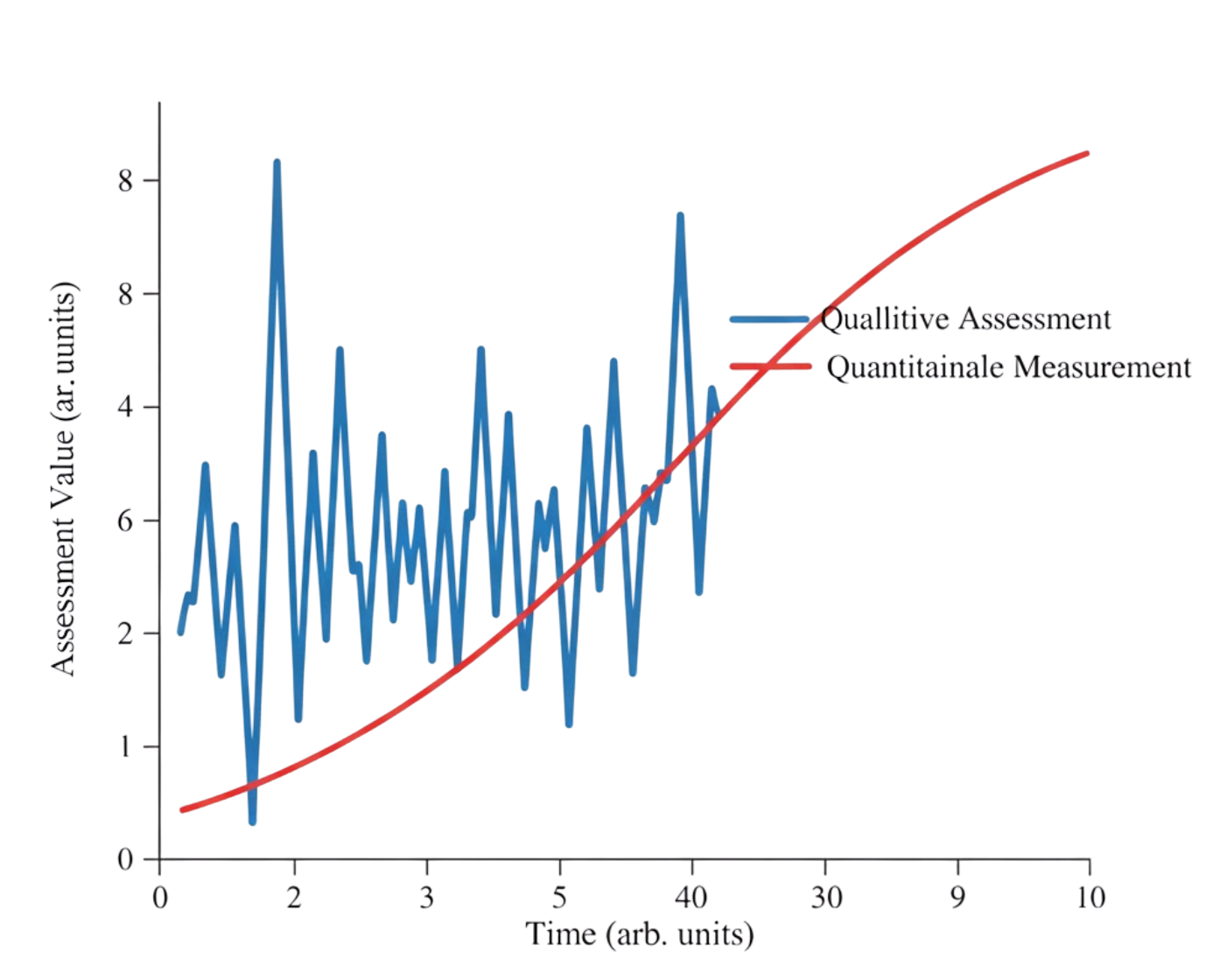

Divergence of Qualitative and Quantitative Measurements Over Time

In 1846, a doctor named Ignaz Semmelweis noticed something troubling. In one ward of the Vienna General Hospital, mothers were dying at five times the rate of the ward next door. It was the same hospital, in the same city, during the same year. The only difference was that one ward was staffed by doctors who came directly from performing autopsies, while the other was staffed by midwives who did not.

Semmelweis did not have germ theory. He did not have a microscope powerful enough to see bacteria. But he had something just as important: he had counted. He had a number. And the number made the invisible visible. When he introduced handwashing with chlorinated lime, mortality dropped from 18% to under 2%. The number did not just describe the problem. It made the solution undeniable.

But here is the part of the story people forget. The medical establishment rejected his findings for twenty years. They did not reject the findings because the data was wrong. They rejected the findings because the profession had no culture of measurement. Doctors operated on reputation, seniority, and judgment. Introducing a number threatened the entire social order of medicine because it implied that a senior physician’s intuition could be proven wrong, and worse, that a junior doctor armed with better data could be proven right. The number was not just a scientific tool. It was a direct challenge to the authority structure that governed the profession. And the authority structure pushed back.

Semmelweis died in an asylum in 1865. Germ theory was not widely accepted until the 1880s. For two decades, the refusal to accept a quantitative finding cost thousands of lives. Not because the answer was unknown, but because the system was not structured to receive a quantitative answer.

This essay is about what happens in that gap. It is not about the moment a number arrives, but about the years before it does, when a system that matters is governed by opinion and the cost of that governance failure remains invisible to the very people responsible for it.

Semmelweis’s story is dramatic, but it is not unique. When you study the history of measurement across critical systems in lending, aviation, food safety, environmental regulation, and cybersecurity, the same pattern emerges so consistently that it starts to look less like coincidence and more like a law of institutional physics. Every time a critical system operates without quantitative measurement, four specific costs appear. They appear in the same order, with the same dynamics, regardless of the industry, the era, or the technology involved.

The first cost is structural inconsistency: Before credit scoring existed, two loan officers at the same bank could evaluate the same applicant and reach opposite conclusions. This was not a flaw in the system. This was the system. Without a shared quantitative reference point, every decision was a fresh act of human judgment, shaped by experience, bias, workload, mood, and variables that nobody tracked because nobody could.

Fair Isaac Corporation studied this phenomenon in the 1950s and found staggering variance in loan decisions across branches of the same institution. The variance was not small. Outcomes that should have been statistically identical were diverging by double digits. The same applicant, with the same income and the same repayment history, could be approved at one branch in the morning and denied at another branch in the afternoon. This was not corruption. It was the natural and predictable result of a system that relied entirely on individual judgment with no standardized measurement to anchor it.

The same dynamic shows up everywhere measurement is absent. In food safety before HACCP scoring, the same restaurant could pass a health inspection in one county and fail in the county next door, because inspectors had no shared quantitative standard for what constituted a violation. In education before standardized assessments, the same student could be classified as “gifted” in one school district and “average” in another, because teachers were evaluating against their own internal benchmarks rather than a common metric. In pain management before the numeric pain scale, the same tibial fracture could receive acetaminophen from one nurse and morphine from another, because pain was described in adjectives rather than measured in numbers.

The deeper problem is not that people made different decisions. It is that nobody could demonstrate the inconsistency was even happening, because there was no consistent metric to compare against. When there is no number, inconsistency becomes invisible. It hides inside the phrase “professional judgment,” and it persists precisely because no one can see it.

The second cost follows directly from the first: accountability disappears. You cannot hold someone accountable for violating a standard that does not exist in quantifiable terms. You can write a policy that says “ensure patient safety.” You can create a governance framework that says “implement responsible AI practices.” But until those principles are attached to measurable thresholds, enforcement becomes a matter of interpretation, and interpretation is the enemy of accountability.

The aviation industry learned this through tragedy. Before the adoption of measurable safety metrics such as hours between incidents, defect rates per flight cycle, and standardized checklists with quantified completion rates, airlines assessed their own safety through self-reporting. The standard was “we follow best practices.” After a crash, the investigation would inevitably reveal that “best practices” meant different things to different maintenance crews, different inspectors, different shifts, and different airports. No one had been lying. There was simply nothing specific enough to be accountable to. The standard existed in prose rather than in numbers, and prose can be interpreted generously by anyone who needs it to be.

The same dynamic plagued corporate environmental responsibility for decades. When the standard was qualitative and every company could simply declare that it was “committed to sustainability,” every company in the world was effectively compliant, because commitment is not measurable. It was only when emissions reporting introduced actual numbers in the form of tons of CO₂, parts per million, and year-over-year change that accountability became possible. This shift did not happen because regulators suddenly became tougher. It happened because there was finally something concrete to hold companies accountable against. You can argue indefinitely about whether a company is “committed to sustainability.” You cannot argue with 47,000 metric tons of carbon.

Measurement does not create accountability on its own. But without measurement, accountability is theater. It carries all the language of oversight, including policies, frameworks, committees, and review boards, but none of the teeth. Because teeth require thresholds, and thresholds require numbers.

The third cost is the most economically significant, and it is also the hardest to see, because it manifests as things that never happen. When there is no number, markets do not crash. They simply never form in the first place.

Before credit scores existed, the secondary mortgage market barely existed either. A bank in Ohio could not sell a bundle of loans to an investor in New York, because there was no standardized way to assess the risk of those loans at scale. Every loan had been originated by a local officer, evaluated using local criteria, and documented in local formats. An investor three thousand miles away would have needed to re-underwrite every individual loan in order to assess the bundle, and the cost of that diligence was prohibitive. So the transaction simply did not happen.

The secondary mortgage market did not emerge because someone invented a clever financial instrument. It emerged because someone gave every borrower a number that an investor three thousand miles away could evaluate in seconds. Credit scoring did not just measure risk. It made risk portable. It created a common language that allowed parties who had never met each other to transact with confidence. A market worth trillions of dollars had been locked inside the absence of a three-digit number.

The same pattern explains why cyber insurance took decades to mature. Until organizations had quantifiable security postures in the form of scores, ratings, measurable controls, and auditable configurations, underwriters could not price policies with any actuarial confidence. You cannot build an insurance market around “we think we’re secure.” Insurance requires a number that actuaries can model, that underwriters can compare across applicants, and that reinsurers can aggregate into portfolios. The number does not just describe the risk. It enables the market infrastructure that makes risk transferable.

When there is no number, entire markets remain latent, not because demand is absent, but because there is nothing to transact around. Buyers cannot evaluate, sellers cannot differentiate, insurers cannot price, investors cannot compare, and regulators cannot benchmark. The market sits frozen, waiting for a unit of measurement that all participants agree to trust. And the longer that wait continues, the more value remains locked inside the gap.

The fourth cost is perhaps the most insidious: improvement becomes impossible to prove. Imagine walking into a hospital board meeting and reporting that patient safety improved this quarter. The first question will be: compared to what? By how much? Measured how? Without a quantitative baseline, improvement is a feeling rather than a fact. You can spend millions on better processes, better training, and better technology and still have absolutely no way to demonstrate that any of it worked.

This is not hypothetical. It is the precise reason the quality movement in manufacturing stalled for years until statistical process control gave factories a way to measure variation and prove that their interventions were actually reducing defects. W. Edwards Deming did not just advocate for quality. He advocated for measurement, because he understood from decades of experience that without it, quality was a slogan rather than a discipline. His famous observation that you cannot improve what you cannot measure was not a platitude. It was an empirical conclusion about what happens when organizations try to get better without quantitative feedback loops.

The consequence of unprovable improvement is organizational paralysis. When the finance team asks whether the governance investment is working and the honest answer is “we believe so but cannot demonstrate it,” budgets get questioned. When leadership asks whether the new training program reduced risk and the answer is anecdotal rather than measured, confidence erodes. And gradually, organizations stop investing in getting better, not because they do not want to improve, but because they have learned that improvement without measurement is indistinguishable from stagnation. The return on investment becomes invisible, and so the investment stops.

What is striking about these four costs is not that they exist, but that the people inside the system rarely see them clearly. Inconsistency feels like professional judgment. Missing accountability feels like flexibility. Frozen markets feel like the market simply is not ready yet. Unprovable improvement feels like doing the best you can under difficult circumstances. The absence of a number is comfortable. It protects incumbents. It allows vagueness to masquerade as strategy. It lets everyone believe they are above average, because there is no average to measure against.

This is why measurement is always resisted before it is adopted. Semmelweis was ridiculed. Early credit scoring was called dehumanizing, with critics arguing that a human relationship between banker and borrower could not and should not be reduced to a number. Standardized testing was called reductive. Emissions reporting was called burdensome. Every number that eventually became infrastructure started its life as an inconvenient truth that the existing establishment preferred to ignore.

And yet, in every single case, once the number arrived and proved its value, the world did not go back. Nobody has argued for returning to gut-feel lending decisions after FICO. Nobody has advocated for removing thermometers from hospitals. Nobody has suggested that airlines stop tracking maintenance defect rates. Nobody has proposed that companies stop reporting emissions in measurable units. The resistance dissolves once the number demonstrates what it can do, because the number does not just measure the system. It reorganizes the system. It changes who has authority, what constitutes evidence, how decisions get made, and what accountability looks like. The number becomes the infrastructure that everything else is built upon.

Which brings us to the present. Today, AI systems are approving loans, diagnosing cancers, screening job applicants, scoring insurance claims, generating legal documents, triaging emergency calls, and making consequential decisions that affect the lives of millions of people across every regulated industry on the planet.

Ask how well these systems are governed, and the answer in most organizations is qualitative. It takes the form of a maturity model with descriptive levels, a readiness checklist with binary checkboxes, a consultant’s assessment delivered as a narrative report, or a regulatory framework mapped onto a spreadsheet that was current when it was created and outdated by the time it was presented. The output is language rather than measurement. “We’re at level 3.” “We’ve addressed most of the NIST categories.” “We’re working on it.”

These are not numbers. They are opinions formatted to look like numbers. And the four costs are already visible for anyone willing to look.

The inconsistency is already here. Two auditors assessing the same AI system against the same governance framework reach materially different conclusions about its compliance posture. This is not a failure of the auditors. It is a failure of the measurement approach, or more precisely, the absence of one. When the standard is a checklist of qualitative criteria, every assessment is an interpretation, and interpretations diverge.

The accountability gap is already here. The EU AI Act is in force. ISO 42001 certifications are underway. NIST AI RMF adoption is accelerating. Regulatory enforcement is not theoretical but operational. Yet enforcement against what baseline? When a regulator asks an organization to demonstrate its AI governance posture over time, the evidence that exists consists of a policy document from last year, a completed questionnaire, and a consultant’s letter. None of these constitute the kind of quantitative, auditable, time-series evidence that regulators in every other domain have learned to require.

The frozen markets are already here. AI insurance is nascent. AI procurement due diligence is a custom exercise every time, with no standardized scoring to streamline vendor evaluation. AI risk assessment in mergers and acquisitions relies on qualitative representations that are difficult to verify and impossible to compare across targets. These markets are not early because demand is low. They are early because there is nothing standardized to transact around. The infrastructure of transaction, including pricing, benchmarking, comparison, and aggregation, requires a number that does not yet exist.

And the inability to prove improvement is already here. Organizations are spending real money on AI governance by hiring responsible AI teams, building review processes, investing in training, and purchasing tools. But when the board asks whether the organization is better governed than it was last quarter, the honest answer is that nobody knows, because nobody can measure it. There is a belief that things have improved. There are actions that should have made things better. But there is no number that moved.

Every critical system in human history has eventually been measured. Not because someone decided measurement was philosophically appealing, but because the cost of not measuring became intolerable. The lending industry crossed that threshold in the 1950s. Healthcare crossed it in the 19th century with the advent of lab science and vital signs. Aviation crossed it after enough planes fell from the sky and enough investigations revealed that “best practices” had been an empty phrase. Cybersecurity crossed it when boards stopped accepting narrative descriptions of risk exposure and started demanding numbers.

AI governance has not crossed that threshold yet. But every signal suggests it is approaching. The regulatory pressure is building across multiple jurisdictions simultaneously. The liability exposure is growing as AI systems move deeper into consequential decision-making. The number of AI systems in production is compounding faster than governance practices can keep pace. And the gap between what organizations claim about their governance posture and what they can actually demonstrate with evidence is widening every quarter.

The question is not whether AI governance will get a number. History is unambiguous on this point, because every critical system eventually does. The question is what happens between now and then, how long the gap persists, how much damage accumulates inside it, and who bears the cost of an industry that governed itself by opinion when it could have governed itself by measurement.

History suggests that cost will be larger than anyone currently inside the gap realizes. It always is.

Until next time,

Suneeta Modekurty

Founder & Chief Architect, METRIS™

Before the Number is a publication about the science of measurement in critical systems.