Why Every AI Problem Is Actually a Data Problem

The Model Is 10% of the Work. The Data Is 90% of the Outcome.

S showed up with a new energy this week. Less confused, more frustrated.

“I’ve been reading,” S said, dropping into the chair across from me. “Papers. Blog posts. Case studies. Everyone’s talking about models. GPT-this, neural network-that, transformer-whatever.”

“And?”

“And I keep thinking about what we discussed. The Amazon hiring tool. The healthcare algorithm. The court system. In every case, the problem wasn’t really the model, was it?”

I smiled. S was getting there.

“The model worked,” S continued. “It did exactly what it was designed to do. It found patterns. It made predictions. It scaled decisions.”

“So what was the problem?”

S paused. Then, quietly: “The data.”

The Dirty Secret of AI

Here’s something the AI industry doesn’t advertise loudly: the model is the easy part.

Building a neural network? There are frameworks for that. Training an algorithm? There are tutorials. Deploying a prediction engine? Cloud providers will do it for you with three clicks.

But the data that feeds those models? That’s where everything breaks.

A 2021 study by MIT and IBM found something remarkable: improving data quality by just 10% often delivered better model performance than any algorithmic improvement.

Not sometimes. Often.

Think about that. Companies spend millions on fancier models, more parameters, better architectures. And a methodical data cleanup would have worked better.

Andrew Ng, one of the most respected names in machine learning, has been saying this for years. He calls it “data-centric AI”. This is the recognition that for most real-world problems, the bottleneck isn’t the algorithm. It’s the data.

“So why does everyone focus on models?” S asked.

“Because models are sexy. Data cleaning is not.”

“That’s it? Vanity?”

“Partly. Also, models are contained. You can point to a model. You can benchmark it. You can publish a paper about it. Data is messy. Data is distributed across systems, teams, years of accumulated decisions. Data doesn’t fit on a leaderboard.”

What “Data Quality” Actually Means

S leaned forward. “Okay, so data matters more than models. But what does ‘good data’ even mean? How do you measure it?”

This is where most conversations go wrong. People treat “data quality” as a vague aspiration, like “innovation” or “synergy.” Something everyone agrees is good but nobody defines.

In reality, data quality has specific, measurable dimensions. Six of them are widely recognized:

1. Accuracy Does the data reflect reality? If your database says a customer lives in Chicago but they moved to Denver three years ago, that’s an accuracy problem. Seems obvious. But in large systems with millions of records, accuracy degrades constantly and… “silently”.

2. Completeness Is the data present? Missing values aren’t just annoying. they’re informative in the wrong way. If 80% of your “income” field is blank, any model trained on that data will learn to work around the gaps. Sometimes in ways you don’t expect.

3. Consistency Does the same thing mean the same thing everywhere? One system records dates as MM/DD/YYYY. Another uses DD/MM/YYYY. One team defines “active customer” as anyone who logged in this year. Another team means anyone who made a purchase. Same label. Different meanings. Model trained on this will learn confusion.

4. Timeliness Is the data current? A credit risk model trained on 2019 data might be useless in 2024. The world changed. Customer behavior changed. The economy changed. But the model is still looking for patterns that no longer exist.

5. Validity Does the data conform to defined formats and rules? An email field should contain emails. An age field shouldn’t contain negative numbers. A country code should match a real country. Validity violations often indicate upstream problems such as poorly designed forms, broken integrations, or manual entry errors.

6. Uniqueness Is each record represented once? Duplicate records create phantom patterns. If the same customer appears twice with slightly different information, the model might learn that these are two different people with correlated behavior. They’re not. It’s just messy data.

“These aren’t abstract concepts,” I told S. “Each one is measurable. Each one has thresholds. Each one can be monitored.”

“But most companies don’t monitor them.”

“Most companies don’t even know these dimensions exist. They think of data quality as ‘does it load without errors.’ That’s not quality. That’s just functioning.”

The Real Cost of “Good Enough”

S pulled out a notebook. I recognized this. It’s the signal that something was landing.

“Can you quantify this? Like, what does bad data actually cost?”

“Gartner estimated that poor data quality costs organizations an average of $12.9 million per year.”

“Average?”

“Average. Some industries are worse. Healthcare. Finance. Insurance. Anywhere decisions are high-stakes and data is distributed across legacy systems.”

But the headline number hides the more interesting story: where those costs come from.

Direct costs:

Rework: Analysts spending 40-60% of their time cleaning data instead of analyzing it

Errors: Incorrect decisions based on incorrect data

Integration failures: Systems that can’t talk to each other because data formats don’t match

Indirect costs:

Missed opportunities: Patterns you can’t see because the data is too noisy

Model failures: Predictions that don’t generalize because training data didn’t represent reality

Compliance violations: Regulatory penalties when data governance requirements aren’t met

Hidden costs:

Eroded trust: Stakeholders who stop believing the numbers

Decision paralysis: Leaders who won’t act because they don’t trust the data

Technical debt: Workarounds that accumulate until the system becomes unmaintainable

“The thing about data quality costs,” I said, “is that they’re distributed. No single failure looks catastrophic. It’s a thousand small problems, each one seemingly tolerable, adding up to systemic dysfunction.”

“Death by a thousand cuts.”

“Exactly. And because no single cut is fatal, nobody prioritizes the bandages.”

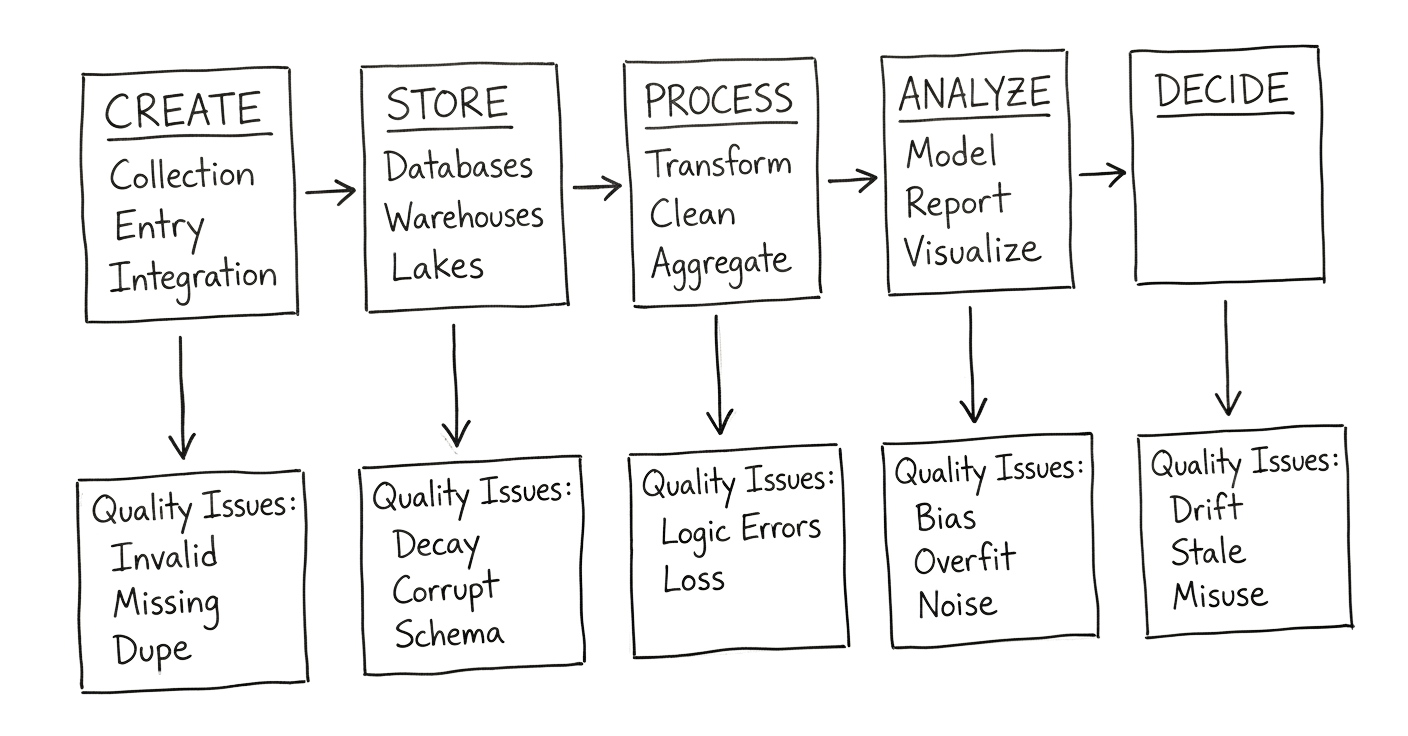

The Lifecycle View

S flipped to a new page. “So where does data quality break down? Is there a pattern?”

There is. And it follows the data lifecycle.

At creation: Garbage enters the system. Bad forms, broken integrations, manual errors, unclear definitions.

At storage: Quality degrades over time. Records go stale. Schemas drift. Corruption happens.

At processing: Transformations introduce errors. Joins create duplicates. Business logic gets misapplied.

At analysis: Models amplify noise. Bias compounds. Overfitting hides problems until production.

At decision: Actions based on bad analysis create real-world harm. And often, that harm generates data that feeds back into the system — creating a loop of dysfunction.

“Every stage is a potential failure point,” I said. “And most organizations only check at one or two stages, usually the ones closest to the final report.”

“So they catch problems at the end, when it’s too late.”

“Or they don’t catch them at all. The decision looks confident. The numbers look precise. Nobody realizes the foundation is sand.”

Why This Is an AI Governance Problem

S sat back. “This feels like a data engineering conversation. What does it have to do with AI governance?”

“Everything.”

There’s a connection here that most people miss. When we talk about AI governance, people tend to think about models, algorithms, and outputs. But if you actually read the major AI governance frameworks (AI governance frameworks like the EU AI Act, NIST AI RMF, ISO/IEC 42001), you’ll find that data is at the center of all of them. This isn’t an afterthought. Data is treated as the foundation.

Take the EU AI Act as an example. Article 10 specifically requires that training, validation, and testing datasets be “relevant, representative, free of errors and complete.” This is not a suggestion or a best practice. It is a legal requirement for any AI system classified as high-risk. If your data doesn’t meet these standards, your AI system is not compliant. It’s that simple.

The NIST AI Risk Management Framework takes a similar approach. It dedicates an entire function to data-related concerns. The framework talks extensively about measuring data quality, documenting where data comes from, tracking how data changes over time, and monitoring for drift that could affect model performance.

ISO/IEC 42001, which is the international standard for AI management systems, requires organizations to demonstrate that they have proper data governance practices in place. You cannot get certified without showing that you understand and control the data flowing into your AI systems.

The message from regulators is clear. If you want to govern AI, you have to start by governing data.“So when regulators come asking about your AI system,” I said, “they’re not just asking about the model. They’re asking about the data. Where did it come from? How was it validated? How do you know it’s still representative?”

“And most companies can’t answer those questions.”

“Most companies have never been asked. That’s about to change.”

The Uncomfortable Question

S closed the notebook. Looked at me directly.

“Data quality is important. It’s measurable. It’s connected to everything downstream. So why isn’t it treated that way?”, She asked.

I’ve thought about this question for years. The answers are unsatisfying but honest:

Organizational silos. Data is created by one team, stored by another, processed by a third, analyzed by a fourth. No one owns quality end-to-end.

Misaligned incentives. Data engineers are measured on pipeline uptime, not data accuracy. Data scientists are measured on model performance, not data completeness. Executives are measured on outcomes, not the quality of inputs.

Invisible failures. When a model makes a bad prediction because of bad data, the root cause is rarely traced back. The model gets blamed. The data stays broken.

Short-term thinking. Fixing data quality is expensive upfront and pays off slowly. Shipping a model is fast and visible. Organizations optimize for what they can see.

“So the system is designed to ignore the problem,” S said.

“The system is designed to optimize for other things. Data quality is a casualty of those optimizations.”

“Until it isn’t. Until something breaks badly enough that people notice.”

“Right. And by then, the cost of fixing it is ten times what it would have been to do it right from the start.”

What Changes This

S asked the question I was waiting for: “So what would it actually take to treat data quality as foundational? Not as an afterthought?”

A few things:

Measurement: The first change is to start measuring at all. There’s an old saying in management: you can’t manage what you don’t measure. This applies directly to data quality. Most organizations don’t measure data quality in any systematic way. They might check it once a year during an audit, or maybe once a quarter when a report is due. But that’s not real measurement. That’s occasional inspection. Data quality changes constantly. New records come in. Old records go stale. Systems get updated. People make errors. If you only look once a quarter, you’re flying blind for three months at a time. What you need is continuous monitoring. That means dashboards that track all six dimensions we discussed: accuracy, completeness, consistency, timeliness, validity, and uniqueness. It also means alerts that notify the right people when any of these dimensions fall below acceptable thresholds. Without this kind of ongoing measurement, you’re reacting to problems after they’ve already caused damage.

Ownership: The second change is to assign clear ownership. Someone has to be accountable for data quality. And I don’t mean “the data team” as some vague abstraction. When everyone is responsible, no one is responsible. You need a specific person with a name and a title who owns data quality. This person needs real authority to make decisions about data standards, data processes, and data tools. They need a budget to invest in the infrastructure and people required to maintain quality. And there need to be real consequences when data quality fails on their watch. If nobody’s job depends on data quality, data quality will always lose to whatever has a deadline attached to it.

Integration: The third change is to integrate quality checks into every stage of work. Data quality can’t be a separate workstream that happens before the “real work” begins. That approach treats quality as a one-time gate you pass through and forget about. Instead, data quality has to be embedded into every stage of the data lifecycle. When data enters a pipeline, there should be automated quality checks. When data feeds a model, there should be validation rules that flag problems before training begins. When data informs a decision, there should be confidence bounds that reflect the quality of the inputs. If the underlying data is shaky, the decision-maker needs to know that. Quality isn’t a phase. It’s a continuous practice that runs alongside everything else.

Incentives: The fourth change is to align incentives. Until data quality becomes part of how people are evaluated, it will always be deprioritized. People focus on what they’re measured on. If a data engineer is measured only on pipeline uptime, they will optimize for uptime and ignore quality. If a data scientist is measured only on model accuracy, they will chase accuracy without questioning whether the training data was reliable. To fix this, you need to tie data quality metrics to the things people care about. Include quality scores in performance reviews. Make quality thresholds a requirement for project approvals. Block model deployments if input data doesn’t meet validation standards. When quality affects promotions, bonuses, and project success, people start paying attention to it.

“That’s a lot of organizational change,” S said.

“It is. And that’s why most organizations don’t do it. They’d rather deal with the symptoms than address the cause.”

“But the symptoms keep getting worse.”

“They do. And at some point, the cost of ignoring the problem exceeds the cost of fixing it. The smart organizations are figuring that out now. Before the regulators force them to.”

Where This Goes Next

S stood up to leave. Paused at the door.

“So we’ve established that AI is fundamentally a data problem. That data quality is measurable. That it breaks down at every stage of the lifecycle. That it’s a governance issue, not just a technical issue.”

“Yes.”

“What I still don’t understand is: how do you actually measure it? Not in theory. In practice. What are the metrics? What are the thresholds? How do you know when something is ‘good enough’ versus when it’s a risk?”

“That’s the language of measurement,” I said. “And it’s more nuanced than most people realize.”

“Next week?” she asked.

“Yes. Next week,” I said.

Next week: The difference between a metric that matters and a metric that misleads, and why single numbers are almost always lying to you.

The data that trains your AI is the foundation everything else stands on. Cracks in that foundation don’t disappear. They propagate.

Download: “Data Quality: The 6 Dimensions” — A visual guide to what data quality actually means and the questions to ask at each stage of the lifecycle.

Download Data Quality: The 6 Dimensions

Founder of SANJEEVANI AI. ISO/IEC 42001 Lead Auditor. 25+ years in AI, data, and compliance across HealthTech, FinTech, EdTech, and Insurance. Building METRIS, the quantitative AI governance platform.